When I was looking for a job in AI last year, I was nervous about making the wrong choice. With the collapse of hot startups like Character, Inflection, and Adept fresh in my memory, I didn’t want to join a sinking ship. I.e., pour years of my life into a vision, only to have that work scrapped.

So I studied the AI startup landscape, interviewed with 46 companies (too many), and chatted with people I admire on how to make a good career decision amidst the noise. In my next three articles, I share everything I learned through this process.

Let’s start with anti-metrics — shiny-but-misleading signals that trap many of us — and an alternative rubric by which to evaluate startups.

section 1. deprioritize these vanity metrics

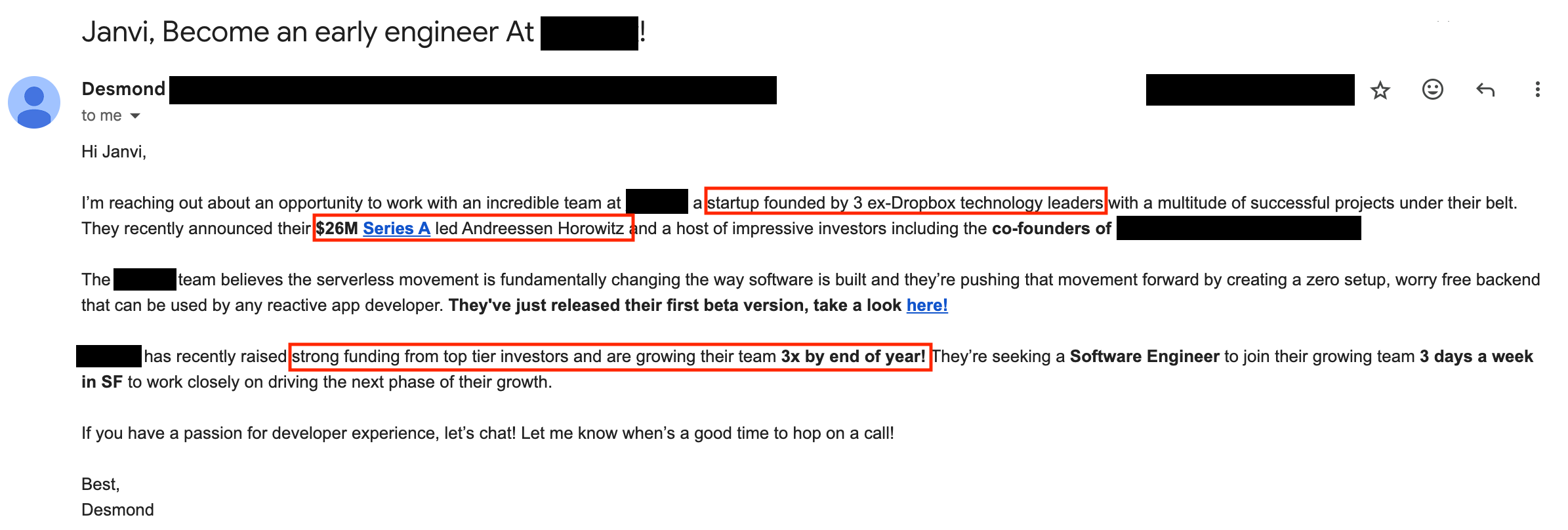

Many companies will try to dazzle you with their billion-dollar valuation, the millions they’ve raised, the elite VCs backing them, and the brand names their founding team worked at. This email is one such pitch:

While these metrics are impressive if you’re the founder who accomplished them, they don't predict a company's success as well as they’re marketed to. Let me explain.

1. elite VCs

Venture capitalists are intelligent people who think hard about which companies are likely to 10x. But even amongst top-tier funds, 3 out of the 4 companies they invest in tank1.

A VC firm can afford these odds because they invest in 10-20 companies every year, and the money they make from their few wins far offsets their losses. Further, these VCs earned their status by making billions off of amazing bets (think: Google). So for them, a couple million dollar investment is pocket change.

In contrast, as an employee, you effectively make 1 bet per year, and you’re very exposed to that bet by virtue of your time and equity compensation.

So while VCs are a great resource for market insights, you can’t blindly trust even the best of them – they don’t have the same exposure to the outcome as you do, and they have different incentives and limitations.

2. millions/billions raised

With money pouring into Silicon Valley, it’s more common to raise money than to actually do good on that money.

Further, if a company keeps raising and diluting equity, after a certain point it can signal that the company isn’t bringing in enough revenue to sustain itself2.

The conditions in which the money was raised make all the difference. Is the company out of cash, or are they raising opportunistically to make bigger bets? Are they diluting equity, or giving employees a chance to liquidate with secondaries?

3. billion dollar valuation

A company’s valuation is determined by a negotiation between founders and lead investors about the company’s estimated future value.

Since it’s not a scientifically derived number, it can be very different from the company’s true future value. They’ve been some recent examples of this in AI, but notable examples pre-AI boom are Humane, Neeva, and Nuro. These companies generated a lot of buzz and were valued at hundreds-of-millions, but the reality has been far from it.

There are many reasons a valuation can be inflated, but two common ones to be wary of are:

Technology hype. Think: Web3, autonomous vehicles, and now AI. Investors don’t want to miss out on the

“technology that will change the world”, so they’re willing to pay more per share, driving up the valuation.Successful, well-networked founders can shop between investors for the number they want. Think Ilya Sutskever’s Safe Superintelligence that is valued at $30B with no product.

It's more important to consider whether a company is positioned to grow their valuation rather than focusing on the absolute valuation itself – more on this later.

4. pedigree of the founding team

While I believe that one should work with the smartest people they have access to, I don’t think pedigree is the best proxy for intelligence and business acumen. Hot take: when people haven’t “made it”, there’s an increased earnestness3 to build something of value. Some examples: Gabe/Winston from Harvey, Brian/Jan from WhatsApp, Amjad Masad from Replit.

And even if pedigree was a good proxy, there’s a lot of nuance: today’s ex-Google is very different from ex-Google 15 years ago.

Ok, so if money raised, elite VC investors, sky high valuations, and pedigree should be deprioritized, what should one pay attention?

Whether the company is in hypergrowth.

section 2. why hypergrowth is the best rubric

To me hypergrowth means: which company will grow the most while I’m there, with the potential of becoming a generational company. In other words, what is the next Meta, Coinbase, Figma, Uber?

I focused on this question, because it has the following effect:

Technical Growth. When users are flooding in, there’s a ton of greenfield feature work and infrastructure challenges – hard, interesting problems usually reserved for senior engineers. This makes you a stronger engineer. You also earn stories of cool things you’ve built.

Increased Responsibility. Hypergrowth entails hiring. The people who’ve been around longer are often tapped to lead projects and teams because they know how the original systems work. A mentor of mine joined a seed stage startup as a mid level engineer, and four years later she finds herself director at the hundred person company.

Future Opportunities. Elad Gil notes that successful companies spawn the next generation of founders and execs4. So when looking for opportunities in five years, you'll have access to the next wave of exciting companies. Case in point: a disproportionate number of OpenAi employees today were early at Facebook and Stripe.

Internalizing what works. You’re privy to some of the key decisions that helped the company scale, and ideally can replicate them in future opportunities.

Financial. Equity grows with the company’s valuation. And hey, it’d be nice to have a home in Mill Valley :)

TLDR: When you're part of a company experiencing hypergrowth, you don't just build your resume — you build the capabilities, network, and stories that shape your career trajectory.

This sounds great in theory, but the catch is that no one knows for sure which companies will 10x from today. You have to make an educated guess, kinda like an investor.

But how? Especially if you’re a software engineer like me: we spend most of our time thinking about code, not doing competitive analysis on startups.

Stayed turned – I answer that in part 2 dropping next week.

Special thanks to Aravind and David for shaping my thinking around this.

Thank you Mathu, Ishaan, Shanks, Abizar for reading drafts of this.

Nuance: hardware and compute-intensive companies will need to raise more money than a SaSS company, and they will also take more time to become self-sustaining.

https://paulgraham.com/earnest.html

banger!! thank you so much for writing this out - most people don't talk about what metrics to ignore and cut through the noise, so so helpful

counting down the days till part 2 is released !!